Drawing fashion is a neglected, almost forgotten art. but, as the work in this book shows, it is as vibrant as any other modern art form and deserves its place as such.

Why should illustrationg fashion be seen as inferior to other forms of drawing? We look at the carefully delineated representations of clothing-especially women’s clothing-in the sketch-books of Rebrandt, bronzino and Holbein and major, although they were often studies for major painted works, they can stand as works of art in their own right.

Fashion drawing as a genre was slow to develop. Dependent on social advancement for its growth, even in the Renaissance, a period of growing richness and grandeur in women’s as well as men’s dress, most clothes were created rather than designed. A member of a royal family or grand lady did not go to couturiers for her wardrobe, making her choice from a selection of sketches instead, her lady companions, working with tailors and mercers, sourced clothes from which she would make a choice; an ambassador or traveller would tell her of the fashion developments in other courts and societies and then she would discuss her ideas wth he tailor, who was almost always male. It was an intimate process requiring no-go-betweens and little contact with anyone outside her immediate household. And, if there were drawings they would usually have been rough sketches or tailors’ technical plans.

This was not an age of shopping, but one of acquiring. For the rich and well-born, shopping did not exist and neither did shops. It was only at the end of the seventeenth century that wealth began to affect the social pattern sufficiently for the middling folk, not aristocrats but middle-class professionals, to be able to dress for pleasure rather than purely for protection or to signify their position in the hierarchy of rank. Projection of one’s status, class and wealth became a legitimate purpose of dress for men and women, and the mode was copied from the tastemakers who hovered in and around the courts.

But many aspiring fashion followers had no direct contact with such people, so how could they know what to wear? They looked for sources of information that were cheap and reliably up to date. And they found them in drawings done at court to illustrate the latest styles being worn by the grand famous. Sold comparatively cheaply, and as times moved forward even hand coloured, these drawings told a woman what she needed to know in order to keep up with the ton at her level.

thus the fashion drawing was born. but it was still rudimentary, even primitive. Early fashion drawings were working drawings for tailors and dressmakers. They made no attempt to set a mood or who clothes in context. They did not set out to seduce the viewer into a world of wealth, power and-to use a word entirely unknown until much later-glamour. They were carefully observed impressions of how a collar was draped, a waist cinched and skirt hung. And if there were few examples of colours or printed fabrics, that was because they were so costly that only the very wealthy needed to know about them.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries drawing fashion developed into a semiautonomous art form as it moved away from its original purpose as a technical aid to become a delineation of all things that go to make a fashionable figure. The popular breed of dog, the parasol in the latest style, the coiffure, millinery and gloves were carefully chosen to create the mood of current fashion. Accessories to the fashionable woman’s toilette-a coach, folly or country seat, a close representation of the most fashionable streets and squares, all helped to build a picture of desire and even envy for eager provincial eyes, as anyone who has read the novels of Jane Austen will know.

But most importantly, the ultimate accessory also began to appear: the man about town, the flaneur, the boulevardier all came into the picture to create the illussion on the page on the fashionable social life lived to the highest level of sophistication and style. In fact, illustrations of the latest modes for men became equally as important as those for women in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

But, in all of them, fashion drawing was secondary, no matter how consummately done. Modern fashion drawing as a legitimate art form in its own right was the product pre-eminently of Paris which, before World War I, shared with Berlin the honour of being the home of European costume-and, it must be admitted, led the field with total conviction. Glamour, sophistication, the new woman: all were introduced to the early twentieth century by these artists, and often with another aspect of modern fashion: humour. Conde Nast and Randolph Hearst published, respectively, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar as society magazines chronicling the privileged not only so that they could enjoy a narcissistic re-run of their social world but, more importantly, to act as primers of behaviour for those who aspired to their eminence. And it was the latter who made the magazines bestsellers, of course.

The first decades of the twentieth century saw the first flowering of fashion illustration as an entity in its modern sense. The business of drawing fashion became a vocation as the dissemination of the latest modes became an increasingly lucrative business. Magazines and folios, often containing work of the highest calibre, were produced not only in Paris-by now the unquestioned center of high fashion-but also in Berlin, London and New York. But the best work came from French-based artists, a situation that continued until the fifties, when the geography of fashion began to swing towards New York and the plutocratic elite who in the eighties would eventually become the legendary ‘ladies who lunch’, whose voracious appetites for haute couture were personified by women like Mona Bismarck who, in 1964, ordered 140 garments from Cristobal Balenciaga.

The first sixty years of the twentieth century, the highpoint and also the slow but hidden decline of fashion illustration, are what the Joelle Chariau collection, illustrated, consist of. And, as you will soon discover as you turn the pages, with a true collector’s eye she has amassed some of the best drawings by some of the greatest fashion illustrators of the last century, some of whom happily carry on in the field; Benito, Lepape, Marty, Erte from the early decades; Berard, Eric and Grau from the mid-century; and Antonio. Mats Gustafson and Francois Berthoud from the period pre-millennium until now.

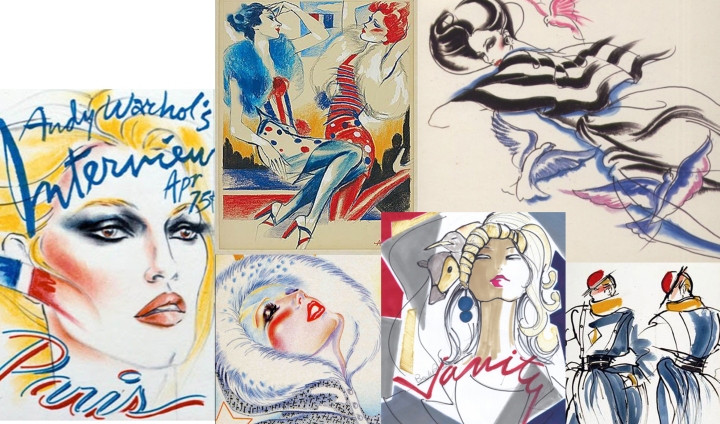

ANTONIO LOPEZ

An illustrator who started out in the mid-60s (when he dropped out of college to work for Women’s Wear Daily), the Puerto Rican-born artist bucked the trend for photography as the dominant medium in fashion media. This was through sheer talent. In his work for the New York Times, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, the whooshes of his lines, movement of his drawings and the confident, sexy poses of the models he depicted gave illustration a reboot. It went from an old-fashioned curiosity to a Technicolor world that everyone wanted to occupy, populated by a glamorous cast of “Antonio girls”. Speaking in the film, the former editor of French Vogue Joan Juliet Back says the illustrator convinced her the “ideal life is lived through a line drawing”.

Lopez lived his life at breakneck speed, putting glamour, decadence, creativity and fun at the heart of everything. Days started and ended late, often at whatever dancing spot played the best disco music at the time. This is all detailed in Sex, Fashion and Disco, with talking heads ranging from Lange and Buck to the much-loved street style photographer Bill Cunningham, a lifelong friend of Lopez, who died shortly after the production of the film ended. The director, James Crump, says that the story of Lopez feels particularly relevant in 2017: “It felt like the right time to do a film, with the political climate as it is at the moment. The fashion world is embracing inclusivity and diversity, and Antonio and Juan [Ramos, Lopez’s longtime collaborator] were advocating that as early as the mid-60s.”

A handsome, sharply dressed man with, we are told, legendary dance moves, Lopez had an inclusive attitude to relationships, dating both women and men. Ramos was his partner for five years and remained his collaborator after their romantic relationship broke down in 1970. His affair with Hall began in Paris in the early seventies, after he was the then-teenage model at a nightclub. Entranced, he put posters around town asking “the American girl” to call him. Lopez accompanied Hall for her 1975 shoot in Jamaica with Norman Parkinson. In the film, American Vogue’s Grace Coddington – the stylist of the shoot – tells of Hall turning up to the airport, during a Jamaican summer, dressed in a full-length fur coat. Such things made sense to an “Antonio girl”.

Lopez and entourage relocated to Paris in 1969, living in Karl Lagerfeld’s apartment, hanging out with the designer and going to the infamous Club Sept every night. It was such a scene that Andy Warhol made a film about it – L’Amour (1973), starring Donna Jordan and featuring Lagerfeld. “They [Lopez and Ramos] had the notion of what the future would be like, when race wouldn’t matter,” says Crump. “They were pushing against the idea that they couldn’t use the models they wanted to use. Paris was more open to their ideas.”

Lopez died in 1987, aged 44, from complications resulting from Aids. Ramos died in 1995. Crump believes that, had their lives not been cut short, the duo would have had as consistent an impact on fashion and popular culture as their one-time friend. “They would engage with [fashion] in the way people of that generation still are, like Lagerfeld,” says the director. “They were so involved in self-imagery, they were very aware of the power of the selfie even before that phrase was invented.”

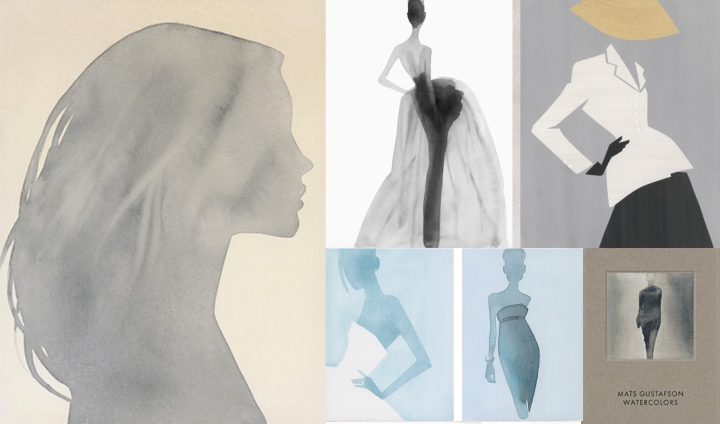

MATS GUSTAFSON

Mats Gustafson is a Swedish artist and fashion illustrator. In his watercolors and paper cut outs, his hallmark style is the simple use of silhouette shapes and muted palettes. His subtle, elegant works can be seen in advertisements and articles for Tiffany & Co., Vogue, and The New Yorker, though most popularly for Dior. In addition to his drawings of archival Dior designs—a collaboration that began in 2013—Gustafson has exhibited internationally in galleries. Born in 1951 in Mjölby, Sweden, he studied at the University College of Arts, Crafts, and Design in Stockholm and the Stockholm Academy of Dramatic Arts before moving to New York. Before reinvigorating the art of fashion illustration, Gustafson worked in stage design. His works are in the collections of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the Roosmuseum in Malmö, and the Nordic Watercolor Museum in Skärhamn, Sweden, among others. The artist lives and works in New York, NY.

With a few deft brushstrokes, Gustafson can capture the subtly undulating curves of a Yohji Yamamoto silhouette or reduce a Romeo Gigli ruffled coat to an almost abstract form with a great deal more eloquence than a digital image ever could. Far from being an anomaly in the post-modern age, Gustafson’s dedication to his craft marks him out as an artisan in the deepest sense. Gustafson protests, “I don’t want to be considered a throwback or a conservative person but I am very content to work with my hands and paper and I’m more inspired by that – I like to see the presence of the hand. It sounds so reactionary really because I try to keep an open eye and mind. But sometimes the shock of the old is more interesting than the contemporary.”

The genre of fashion illustration may have all but disappeared now (with a few notable exceptions) but it was once a crucial element of luxury advertising – rising to prominence in the 1920s with the seminal Gazette Du Bon Ton and again in the 80s with the late Anna Piaggi’s revolutionary Vanity magazine. Antonio Lopez’s ultra-glamorous drawings leapt off the page and caught the eye of a young Gustafson growing up in Sweden, who says “that triggered something in me that made me think I could do this.”

More recently, following in the footsteps of the revered 40s illustrator Rene Gruau, he has collaborated with the house of Christian Dior, now under the stewardship of Raf Simons. In Simons, Gustafson has found a kindred sensibility that chimes with his own – “I do like Raf’s sense of clean, modern. He has a lot of references to Dior but he can do that without a trace of nostalgia – it’s a very pure and intellectual conversation he has with the house of Dior and I’m intrigued by his vision.” In attempting to get to “the essence of design”, Gustafson’s ethereal watercolour, pastels and cut out paperworks eschew trends, achieving something far more meaningful instead, in order to fulfill his aim to “make my fashion drawings not just something to consume but something you could look at the next day and have a longer life.”

It’s this search for a timelessness that has seen a shift in his personal work to working with different subject matter, displayed in the limited edition monograph, Mats Gustafson: Watercolors, a selection of his work from 1989-2001, reissued to coincide with his exhibition – from majestic landscapes to lyrical depictions of deer and swan and a series of nudes that evoke lust and fragility at the same time. Working in this way has allowed Gustafson to continually challenge himself, “I needed to do my own work to counteract the fashion work but each has influenced the other and it was a way for me to grow as an artist.” His exquisite oeuvre betrays an unashamedly romantic spirit, albeit one tinged with a sense of melancholy. He shrugs, “Well that’s the Scandinavian aspect of me I guess. Romantic, I have no problem with that – I’m a sucker for beauty. Fashion is not always about beauty but to me it is – when it works, it really is about beauty.”

FRANCOIS BERTHOUD

Berthoud was born in Le Locle, Switzerland. After finishing his studies at the School for Graphic Design in Lausanne in 1982, Berthoud went to Milan where he drew cartoons for Alter-Alter and Linus. Early fashion illustrations were commissioned by Anna Piaggi for Condé Nast’s Vanity and since then his work has appeared in many of the leading fashion magazines such as Vogue, Numero and Interview to name just a few.

Berthoud is fêted by the world’s finest creative directors for producing images of the female form that possess an exacting precision and are imbued with a latent eroticism.

Berthoud’s career has been largely spent working out of a studio in Milan. In 2007 he returned to Switzerland and set up a studio in Zurich.

As an illustrator, Berthoud’s aim is to “interpret fashion in a more conceptual way – it is the opposite of photography to show fashion’s bigger picture.” Far from coolly abstract though, a latent eroticism pervades his work, none more apparent when he provided delicate illustrations for Betony Vernon’s The Boudoir Bible, an experience he enjoyed very much, “I had to find a specific visual language because of the content of the images. I opted for simple pencil drawings, sharp enough for killer details but also soft and delicate, capable of rendering the flesh.” After all he says with a wink, “Fashion is seduction and seduction is sexual. Arts, Eros and death are the universal topics!”

For more than 25 years, the celebrated Swiss-born illustrator, Francois Berthoud has been capturing the volatile fashion world in a variety of materials, the images linked only by their creator’s willingness to experiment. “Fashion is a testimony of its time,” says Berthoud. “My pictures for fashion have evolved through the decades, as the moods changed.”

AURORE DE LA MORIENERIE

Paris-based Aurore de La Morinerie was born in 1962 in Saint-Lô, France. After graduating from the Ecole des Arts Appliqués Duperré in Paris in the 80s, she began her career as a fashion designer. Later on she spent two years studying Chinese calligraphy that became a very formative influence on her style and which also taught her concentration, strength and rapidity of execution. Extended travels in China but also in India, Japan and Egypt have allowed her to deepen her artistic skills and refine her drawing technique.

For the past 20 years Aurore has been pursuing a career as a very successful fashion illustrator, and she is regularly illustrating for Le Monde, ELLE, Harper’s Bazaar, as well as for advertising campaigns and various publishing companies. Aurore has also been working for many prestigious fashion houses, for example Hermès, Margiela, Cartier, Issey Miyake, and lately for big clients like H&M, IKEA, and the Parisian department store Printemps.

Aurore mainly draws with watercolor, ink and wash painting, but she is also working with a traditional etching press for monotypes technique to create a more graphic art.

Beside her sophisticated fashion silhouettes, Aurore also loves to draw elements from the nature; landscapes, animals, plants. In 2011 she was invited as “artist-in-residence” aboard Tara between the Galapagos islands and Ecuador, resulting in a beautiful serie of monotypes of planktons. Aurore’s illustrative monotypes have recently been exposed at the Palais Galliera, the Fashion Museum of Paris, for the retrospective exhibition of the work of the couturier Azzedine Alaïa.